Preventing Supply Chain Strain

Can bringing manufacturing home be the answer to the challenges of global production?

BY REBECCA MITCHELL, CFA

Vice President

Most of us would prefer to forget the early days of the pandemic, but I carry some of those memories with me. I remember my first time going to the grocery store after health officials recommended wearing face coverings.

I ran into one of my colleagues at a Reasor’s Foods who was wearing a blue bandana across her face, as if she had stepped out of an old Western movie.

What stands out even more in my memories was my most bizarre trip to Target. When the store opened, about a dozen other customers joined me in grabbing carts and walking in a single-file line through the quiet aisles to the paper products. Most of the shelves were bare except for one bay holding the greatest prize of 2020: toilet paper. Each customer took one, as the sign above directed them.

While consumers’ fears early in the pandemic caused some of the shortages outlined above, the shortages of toilet paper and other necessities revealed an actual problem in our nation’s supply chains. We had globalized to an extreme efficiency level, but it put us at risk of not having the necessary things, especially in times of upheaval.

How We Embraced Globalization

If you’ve ever been in an economics class, you probably covered the concept of comparative advantage. The principle states that one entity (country, company, etc.) can produce certain goods at a lower opportunity cost than its trading peers. Opportunity cost can mean the cheapest cost, but it also considers other items a producer could use resources to make. Conversely, different entities will be more efficient at producing different goods. By partnering, countries can take advantage of these benefits by trading.

The last half of the 20th century saw the dismantling of trade barriers and the rise of free trade agreements. Countries began to work together to maximize their comparative advantages.

Several trade agreements developed into the World Trade Organization, established in 1995, which was pivotal in fostering this interconnectedness. Technological advancements in communication and transportation further facilitated the movement of goods and services across borders.

Developing economies like China attracted companies looking for cheaper labor and production capabilities. In addition to lowering production costs, offshoring portions of supply chains allowed companies to introduce themselves to new consumers worldwide. Consumers also benefited from a wider variety of goods offered at lower prices.

Where We Are Now

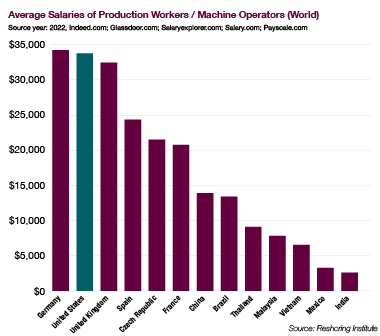

While the conversation about reshoring manufacturing in the U.S. increased during the pandemic, previous events displayed vulnerabilities in global supply chains.

The 2008 financial crisis exposed vulnerabilities in globalized supply chains, leading to calls for greater self-reliance. The economic instability of other countries during the crisis impacted companies’ supply chains.

Additionally, it became apparent that outsourcing production came with sacrifices, including increased communication and transportation costs and the loss of intellectual property. The global financial crisis also coincided with high unemployment in the U.S., and reshoring offered a way to create jobs here.

The U.S.-China trade war further strained the relationship between the two economic giants, raising concerns about reliance on a single source for critical goods. In 2018, the Trump administration began investigating China’s intellectual property practices, and each country began imposing a series of tariffs on the other. While the first phase of a trade deal was signed in 2020, the Biden administration has continued to have concerns surrounding trade with China.

In addition to the pandemic, these events shed light on global supply chain weaknesses and pushed governments and companies to reflect on the benefits of making supply chains less complex and bringing them closer to home.

Friend-Shoring, Near-Shoring, Reshoring

A 2021 survey conducted by Kearney found that 92% of U.S. manufacturing executives had considered reshoring or had moved some manufacturing operations closer to home. The survey also found that 70% of CEOs with manufacturing in Asia were considering moving production to Mexico, Canada, or Central America.

Additionally, a Thomson Reuters’ Global Trade report surveyed 200 global trade professionals, and 78% agreed that global multinational firms should diversify supply chains by expanding through local sourcing or near-shoring.

Friend-shoring is moving production to countries allied with the United States. The war in Ukraine and continued conflict between the Chinese and United States governments are significant catalysts for the U.S. to seek places to produce goods other than China, even though China has been a leading exporter to the United States for some time.

Other Southeast Asian countries are some of the biggest beneficiaries of U.S. companies moving production out of China. While not formally allied, Vietnam and the United States entered a strategic partnership in 2023, and Vietnam has seen an increase in production partnerships with U.S. companies.

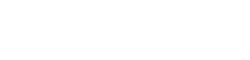

Vietnam is an attractive production hub for several reasons. Vietnam’s labor costs are about half of Chinese labor costs. In 2020, the average labor cost in China was approximately USD 6.50/hour, compared to USD 2.99/hour in Vietnam.

Additionally, the labor force is relatively large and well-educated, and the Vietnamese government has passed legislation to further invest in training its workforce. Vietnam also has several international airports, seaports, and rail links facilitating production flow.

For U.S. trade, Mexico has been a big beneficiary of near-shoring. Many factors that make Vietnam an attractive production destination also make Mexico a beneficiary of changing supply chains. Its wage cost advantages are similar to those of several Asian manufacturing locations.

Unlike Vietnam, Mexico offers additional benefits to companies because of its proximity to the United States. Sharing a border allows for reduced transportation and logistics costs. In March 2023, the U.S. Surface Transportation Board approved a merger of Canadian Pacific Railway Limited and Kansas City Southern Railway Company. This merger created the first transcontinental railroad that linked Mexico, the U.S., and Canada, offering a streamlined route for products leaving Mexico headed north.

Proximity also allows companies to establish warehouses and logistics facilities to keep inventory closer to home, helping to avoid supply shocks like those seen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Partnerships with Mexico directly relate to efforts to bring production back to the United States. Due to their proximity to Mexico, Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico are seeing additional investment.

Arizona has become a beneficiary of reshoring and the Chips and Science Act. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is building facilities to produce its semiconductor chips in the U.S. Other companies, including Micron Technology, Samsung, and Texas Instruments, have also announced plans to build semiconductor manufacturing facilities in the United States.

Much of this reshoring is due to the support companies are receiving from the Chips and Science Act. The $280 billion plan has encouraged companies to invest in semiconductor manufacturing in the United States and has urged universities to increase educational opportunities related to semiconductor manufacturing.

The act creates opportunities in different regions, creating clusters similar to Silicon Valley, where universities and companies collaborate. These plants also allow for a competitive advantage in shortening the supply chain, creating logistical efficiencies, and encouraging foreign direct investment in the United States.

Not Leaving China Altogether

While the tension between China and the U.S. has been an increasing catalyst for U.S. companies to shift production, not all production is leaving China. Many companies are focused on diversifying their supply chains, including keeping some production in China.

Additionally, China-based manufacturing companies are also expanding their production to other countries. In other words, there is still ample opportunity for U.S.-China partnerships in production; those partnerships simply change in function and location. This business strategy has been named the “China Plus One” strategy.

In Conclusion

This article merely scratches the surface of the changes we see in our supply chains. Reshoring and diversifying supply chains can increase national security, create more resilient supply chains, and meet changing consumer preferences by offering greater transparency in production.

It is also expensive to develop new production facilities. It requires continued investment in infrastructure from countries experiencing an increase in manufacturing industries and time to build new facilities and shift production.

Infrastructure investment means increased capital expenditures and a lag time in realizing efficiencies. Advancements in automation and technology can support these transitions. However, continued cooperation between countries is needed to support these changes in the global trading system.

REBECCA MITCHELL, CFA

Vice President

(918) 744-0553