WHEN INSTINCTS GO WRONG:

OVERCOMING BEHAVIORAL BIASES

By Zac Reynolds

One of the fascinating aspects of managing wealth for individuals is getting to watch the wide range of human emotions play out in real time. Often, different clients react to the same event in diametrically opposed ways. Many clients will see the market drop on fears over the latest Trump tweet or North Korean nuclear test and have the impulse to sell in order to protect from further losses. A smaller number of clients will sense an opportunity to buy assets at lower prices.

Both reactions are understandable. However, one response is clearly more likely to lead to success over time. The “sell first and think later” response is driven by what Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman calls System 1 thinking – fast, intuitive and emotional. In his bestselling book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Kahneman shows how System 1 thinking is great for many human activities – everything from driving a car on an empty road to automatically knowing the answer to simple equations like 2 + 2.

System 2 thinking, on the other hand, is slow, deliberate and requires conscious effort. It’s the type of thinking required for more complex equations, like 17 x 24, or making a left turn into dense traffic (both examples from Kahneman’s book). Most importantly, it is less prone to error, making it the better system of thinking when it comes to most investing decisions.

The discoveries of researchers like Kahneman help explain why many predictions of traditional economic theory turn out to be incorrect in the real world. The problem lies with classical economists’ assumption that people act in rational ways to maximize wealth. One needs look no further than the Dutch tulip bulb mania or the Beanie Baby craze of the 1990s (and perhaps the price of Bitcoin today) to find examples of human emotion overriding rational behavior.

The combination of traditional economic theory with human psychology led to the relatively new field of behavioral economics. Practitioners of this new science discovered that human irrationality isn’t random – we are wired in a way that makes us susceptible to predictable patterns of irrational behavior.

Behavioral economists have separated these behaviors into two main types – emotional biases and cognitive errors. Emotional biases spring from impulse or intuition, and can be difficult to correct – after all, we can’t really help the way we feel. We can, however, recognize when certain feelings occur and do our best to avoid making decisions based on feelings alone. Cognitive errors are the result of subconscious mental “shortcuts” or blind spots in the human mind. These sorts of errors are more easily corrected than emotional ones, mainly through better information, education, and the use of System 2 thinking.

As identifying the problem is always the first step toward a solution, let’s examine a few of the common errors people make when it comes to investing.

EMOTIONAL BIASES

Loss-Aversion: Highly relevant to investing, loss-aversion bias was first identified by Kahneman and his partner Amos Tversky in 1979. They observed that people tend to strongly prefer avoiding losses as opposed to achieving gains. In simpler terms, most people feel about twice as much pain from losing money as they do pleasure from gaining an equivalent amount. We see this behavior often as some clients will scan their investments and quickly focus on individual securities trading at a loss. Often, there will only be a few securities in the red versus dozens of securities with gains. Still, System 1 thinking takes over and people will react emotionally even to the pain of unrealized losses.

By slowing down and engaging in System 2 thinking, most people will recognize that in a diversified portfolio, there will usually be some out-of-favor stocks. It’s the total portfolio gain that counts – not any one security.

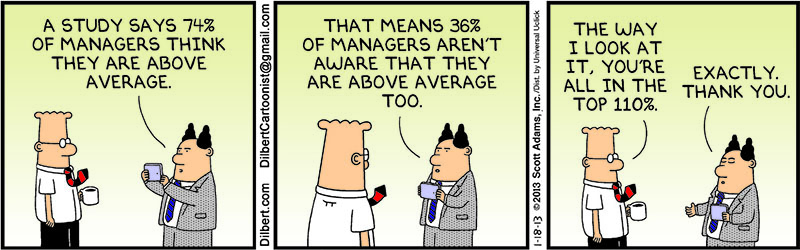

Overconfidence: Perhaps one of the most difficult biases to recognize in oneself, overconfidence is nonetheless potentially destructive to wealth. Studies show people generally do a poor job of estimating probabilities, yet still believe they do it well because they are smarter and more well-informed than they actually are. The same phenomenon causes 90% of drivers to consider themselves above average. Logically, of course, we know that a huge number of drivers are, in fact, below average.

DILBERT ©2013 Scott Adams. Used By permission of ANDREWS MCMEEL SYNDICATION. All rights reserved.

Overconfidence often causes individuals to construct portfolios that are overly concentrated in one stock or sector. They may think they have an insight or edge and ignore the risk that is created by failing to diversify. Another common case: employees who invest the majority or all of their retirement savings in their employer’s stock. They believe because they are inside the organization, they have greater control over how the company will perform. Sadly, former employees of companies like Enron and WorldCom found out how little control they actually had.

Regret-Aversion: This is the tendency to avoid making decisions that they fear could lead to regret in the future. Oftentimes this will lead to people being “frozen” after sharp moves up or down in the market. If the market has fallen significantly, the fear instinct kicks in and people are afraid they will invest only to see the market move down further. Conversely, if the market has had a strong run (as is the case today), fear of investing right at the top can keep investors out of the market and on the sidelines.

A good strategy for overcoming regret-aversion is creating a plan and sticking to it. For example, those who have their 401(k) contributions automatically withheld from each paycheck are much less likely to alter their investments after sharp moves in the market versus those who are manually making contributions.

COGNITIVE ERRORS

Hindsight: This is the bias behind the phrase “Hindsight is 20/20.” Meaning, of course, that it is easy to see the right course of action with the benefit of hindsight. This is a dangerous bias, though, because it leads people to believe that what did happen was inevitable, or the only possible outcome. In reality, what did happen was one of many possible outcomes.

Think about this as a game of chance. If someone flips a coin and lands on heads five times in a row, we know that is an unusual result – something that should only happen about 3% of the time. We also recognize that an outcome of three heads and two tails was just as possible (and indeed more likely). We don’t assume that the flipper of the coin is highly skilled at flipping heads – only that chance or luck led to an unusual result. Predicting the future, whether it is the path of a hurricane or the performance of a stock, is an inexact science. A forecaster can incorporate all the information available and still be wrong. Or make a wild forecast and be right due to luck. It requires a large sample size of predictions to discern between luck and skill.

Confirmation bias: Some people tend to seek out information that confirms their preconceived notions and to ignore or undervalue information that contradicts their beliefs. Examples abound, inside and outside the investing world. Think of your diehard Republican friend who only watches Fox News or your liberal relative who gets all her news from MSNBC. Neither person is likely to have their beliefs challenged. At TCO, one tactic we use to combat confirmation bias is to ask portfolio managers to lay out a bear case as well as a bull case when considering a particular investment. By fully examining both sides of the argument, we are less likely to fall victim to this bias.

COSTLY ERRORS

Identifying mistakes is the easy part. Recognizing them and consciously changing a behavior to be more rational is more challenging. Making the effort to engage in more System 2 thinking should certainly pay off, though, as studies from Vanguard and Morningstar estimate that behavioral investing errors cost investors around ±2% per year in lower returns versus the overall market. Those lower returns can be attributed to poor timing decisions – namely buying high and selling low, often due to behavioral errors. Working with a professional money manager means having someone who can recognize and mitigate these emotional biases and cognitive errors.

Of course, if you made it through this article, you are clearly well above average and immune to any of the biases that affect lesser humans. Congratulations!