Fleeting or Forever?

Evaluating Whether Inflation Is Temporary or Here to Stay

By Tim Hopkins

When I first became interested in investing and financial markets (more years ago now than I care to admit), I made it a regular practice to watch “Wall Street Week with Louis Rukeyser” every Friday night on public television. One of Rukeyser’s frequent guests was the late Martin Zweig, a well-respected investor, investment adviser and financial analyst. I remember well one episode in which Rukeyser asked Zweig which economic indicator he believed to be most important to monitor. Without hesitation he replied, “inflation.” He went on to explain that because one of the mandates of the Federal Reserve (Fed) is to maintain a stable price environment, and because the resulting monetary actions of the Fed have such an important influence on the economy and financial markets, inflation in his opinion was the single most important factor to watch.

Ever since the 2008 global financial crisis and the Fed’s extreme monetary policies in response, economists and central bankers have continually warned about the risks of inflation. Yet over the last four decades, inflation declined substantially, from 7.4% in the 1970s to a mere 1.8% in the 2010s. The 2.0% inflation target established by the Fed in 2012 has rarely been breached. Near-zero interest rates and supportive fiscal policies have led to predictions of possible runaway inflation, but instead it has remained stubbornly low.

RISK TO FINANCIAL MARKETS

Recently, however, concerns about inflation have been rising. According to Bank of America/Merrill Lynch’s widely followed survey of global investment managers, inflation is now seen as the greatest risk to financial markets, ahead even of the pandemic. A significant and lasting speedup in inflation would damage the U.S. economy, affecting consumers’ buying power and future economic growth. It would also be a risk to buoyant financial markets by putting upward pressure on interest rates.

The April Consumer Price Index (CPI) showed prices surged by the most in any 12-month period since 2008. The data partly reflects a recovery that is picking up steam as the pandemic eases. Many consumers emerged from the pandemic with enhanced buying power thanks to stimulus checks and savings accumulated during lockdowns. In a sense, that has created increased demand for more items than companies still attempting to reopen can currently supply.

A combination of rock-bottom interest rates, the Fed purchasing $120 billion per month of U.S. Treasury/Agency bonds and aggressive fiscal spending may be compounding the problem, against a backdrop of labor shortages, increasing transportation costs and supply chain disruptions that have been seen across many areas of the economy.

REBOUNDING FROM PANDEMIC RESTRICTIONS

While the directional change in consumer prices in April was broadly expected by economists, the magnitude of the increase was well above expectations. According to the Labor Department, the CPI jumped 4.2% from April 2020 to April 2021. On a month-to-month basis, which strips out the effects of price declines in last April, prices rose 0.8%, far above consensus expectations of 0.2%. Core CPI (excluding food and energy) rose an even larger 0.9%, the most since September 1981. Used car prices spiked 10% in April compared with March, accounting for more than one-third of the overall increase, according to the Labor Department.

Almost all of the April CPI increase was driven by outsized increases in sectors that are seeing demand recover as pandemic restrictions ease. Airline fares rose 10.2% from March to April, hotel prices were up 7.6%, and car rental prices jumped 16.2%. So far, these price increases are seen as a reversal in prices from early in the pandemic.

Surging car rental prices reflect limited supply as rental agencies are now rebuilding previously slashed fleets, driving up the prices of both rentals and used vehicles. Depending on the strength of pent-up demand for leisure and travel, similar price increases may occur in other categories over the coming months.

The May CPI shows that headline consumer prices rose 5% year-over-year in May, higher than Wall Street expectations. The 3.8% rise in the core inflation rate was the largest increase in nearly three decades. Categories sensitive to pandemic reopening dominated price pressure for a second straight month, with an estimated 52% of the month-over-month increase coming from only six components: used cars, rental cars, vehicle insurance, lodging, airfares, and food away from home.

Recent inflation measurements are affected by comparisons with the figures from early in the pandemic when prices dropped steeply as demand collapsed for many goods and services during lockdowns. These “base effects” and the broad macro environment suggest to some that the surge in inflation will be mostly “transitory,” with inflation expected to fall back to target next year as base effects fade, supply bottlenecks ease, and the current increase in suppressed demand runs out of steam. This is the view shared by the Biden administration and members of the Fed.

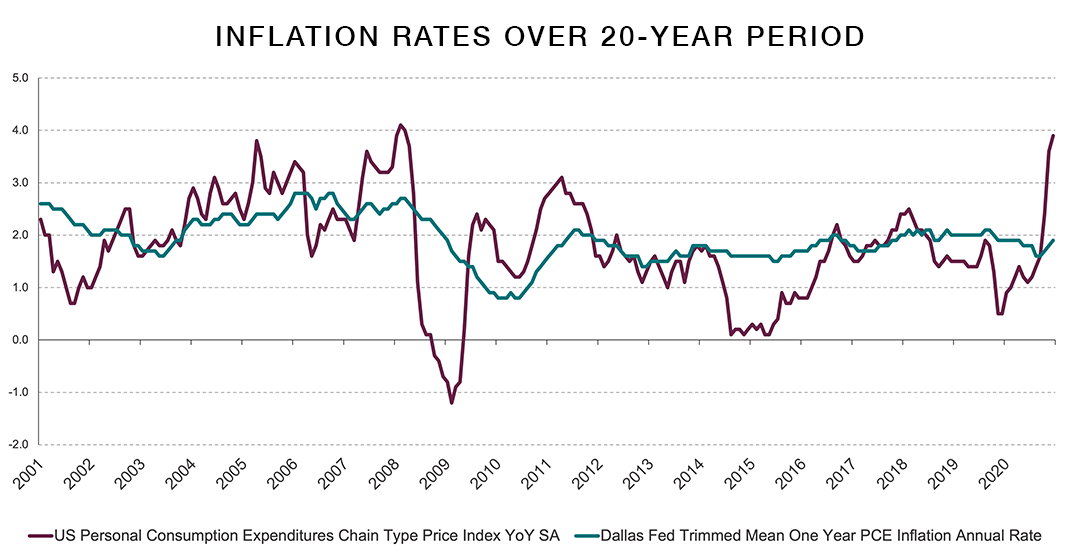

PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures): A country-wide indicator of average price changes in all categories of personal consumption. This measure is calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures): A country-wide indicator of average price changes in all categories of personal consumption. This measure is calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Trimmed Mean PCE: A measure of PCE that trims the most extreme observations, both highest and lowest, from the data in each period. Then, the inflation rate is calculated as a weighted average of the remaining elements. This measure is calculated by the Dallas branch of the Federal Reserve.

Source: Bloomberg, LP. (Root source: Bureau of Economic Analysis/Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas)

WAGES AND UNEMPLOYMENT

Concerns about inflation often center on wages. Labor is usually a company’s biggest expense, and employers can be reluctant to raise wages because reversing course usually isn’t realistic. Many in the “inflation is transitory” camp point out that while the unemployment rate declined significantly to 5.8% as of the time of this writing from the peak of 14.8% last year, it is still higher than the pre-recession low of 3.5%. They believe this unemployment gap will limit compensation growth and inflation.

However, those who take the opposite view also point to wage/labor market issues to support their stance. They cite data that show wages and benefits grew quickly for U.S. workers in the first quarter of 2021, a sign that businesses are starting to offer higher pay in order to fill available jobs. U.S. workers’ total compensation rose 0.9% in the first quarter, the largest gain in more than 13 years, up from a 0.7% increase in the fourth quarter of 2020.

The May National Federation of Independent Business survey paints a similar picture. The share of small firms reporting that jobs are hard to fill climbed to a record high of 48% in May, suggesting that labor market conditions might be far tighter than the elevated 5.8% May unemployment rate would imply. Filling vacancies for low-wage and hourly workers is especially a challenge. Many firms have had to increase pay or offer signing bonuses to attract applicants.

Those who expect inflation to persist note that central banks, led by the Fed, are less concerned about inflation now than in the past. At a recent news conference, Fed Chairman Jay Powell reiterated that the central bank will be in no rush to remove monetary stimulus even if inflation accelerates above its 2% target. In August 2020 the Fed even adopted a revised target of average inflation of 2%, meaning the Fed will be comfortable with it overshooting 2% for an unspecified period of time to make up for the past decade’s misses.

In addition, fiscal policy has shifted. Instead of worrying about rising federal debt, many economists expect aggressive action to offset shortfalls in demand. As a result, Congress likely will not remove fiscal stimulus as quickly as it did following the 2008 financial crisis. That abrupt removal led to a disappointingly slow recovery, which no one has been eager to repeat.

CONSUMERS COULD DRIVE INFLATION

In the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment survey released in June, inflation remained a top concern of consumers. For the next year, consumers expect prices to increase by a relatively high 4%. The risk is that as inflation expectations rise, they become embedded in consumer behavior and business decisions. Workers may demand higher wages to keep up with prices. Businesses pay to keep those workers, then raise prices to maintain margins.

INFLATED CONCERNS?

The majority of economists and investment strategists seem to agree with Powell and the Fed that the recent surge in prices is temporary due to the acceleration in economic growth caused by the reopening of the economy and that once growth returns to a normal pace, the inflationary pressures will subside.

However, higher and longer lasting inflation than currently expected could cause the Fed to raise interest rates faster and higher than financial markets anticipate. In a June 16 press conference, Powell said, “As the reopening continues, shifts in demand can be large and rapid, and bottlenecks, hiring difficulties and other constraints could continue to limit how supply can adjust — raising the possibility that inflation could turn out to be higher and more persistent than we expect.”

It is generally thought that it will be several more months before it’s clear whether the current period of rising prices is temporary or not. The one thing that does seem certain is that, as Martin Zweig stated many years ago, inflation will be the most important economic indicator to monitor for the foreseeable future.

Tim Hopkins, CFA

Senior Vice President

(405) 840-8401

THopkins@TrustOk.com